Divan

Announcing Divan!

Divan is a Rust framework for quick comfy benchmarking, featuring:

Divan currently has 1060 GitHub stars and is used by 793 projects.Get started easily with examples that span from introductory to advanced scenarios. The entire example benchmark suite compiles and runs in 40 seconds on my machine. It is also benchmarked in CI.

I’m open to hire for Rust work! Please reach out at hire@nikolaivazquez.com.

Compared to Criterion

The current go-to Rust benchmarking library is Criterion.rs, a port of Haskell’s Criterion. It works very well and has many useful features.

However, I believed we could have a simpler API while being more powerful, such as benchmarking generic functions and measuring allocations.

Follow Along

Run these benchmarks locally! Steps:

-

Clone the repository:

git clone https://github.com/nvzqz/divan.git cd divan/examples -

Open

divan/examples/benches/scratch.rsin your editor:fn main() { divan::main(); }This can be run with:

cargo bench -q -p examples --bench scratch

Usage

Examples

Divan has many practical examples. These can all be benchmarked locally with:

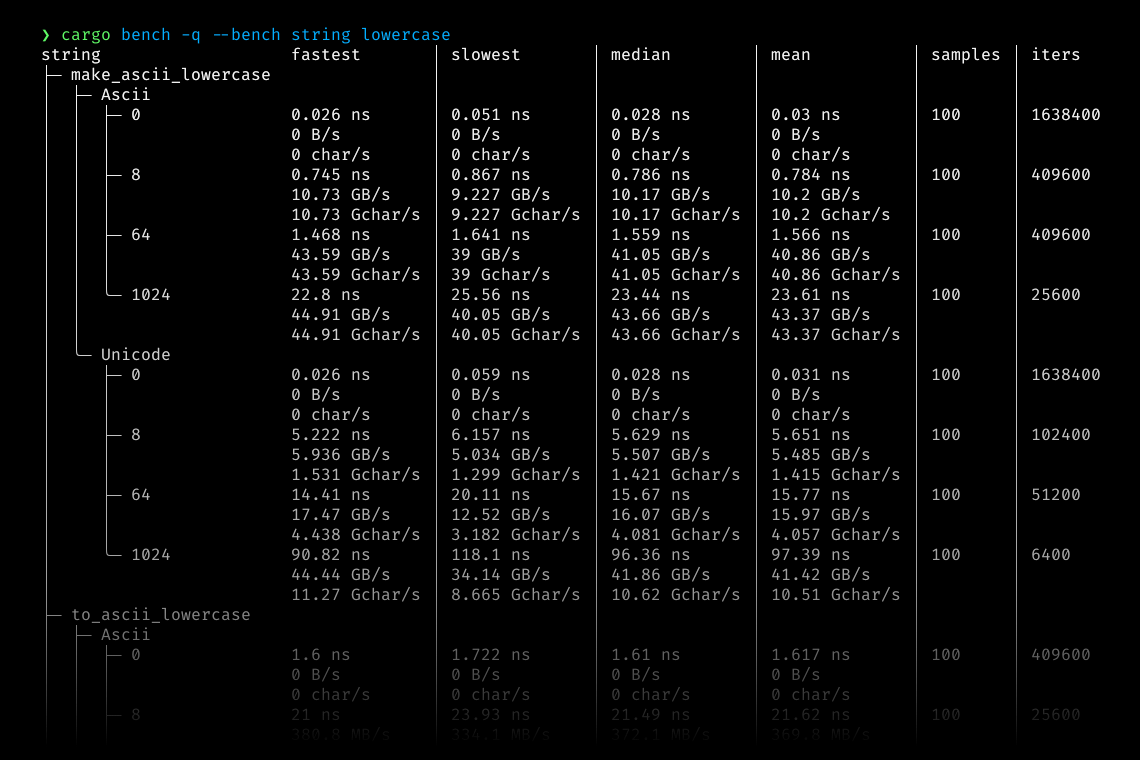

cargo bench -q -p examples --all-featuresEach example file can also be run on its own. Run the string.rs benchmarks with:

cargo bench -q -p examples --bench stringstring fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

├─ char_count │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─ Ascii │ │ │ │ │

│ │ ├─ 0 0.926 ns │ 1.069 ns │ 0.967 ns │ 0.964 ns │ 100 │ 409600

│ │ │ 0 B/s │ 0 B/s │ 0 B/s │ 0 B/s │ │

│ │ │ 0 char/s │ 0 char/s │ 0 char/s │ 0 char/s │ │

│ │ ├─ 8 2.157 ns │ 2.341 ns │ 2.238 ns │ 2.225 ns │ 100 │ 204800

│ │ │ 3.708 GB/s │ 3.417 GB/s │ 3.574 GB/s │ 3.595 GB/s │ │

│ │ │ 3.708 Gchar/s │ 3.417 Gchar/s │ 3.574 Gchar/s │ 3.595 Gchar/s │ │

│ │ ├─ 64 3.703 ns │ 4.049 ns │ 3.744 ns │ 3.766 ns │ 100 │ 204800

│ │ │ 17.28 GB/s │ 15.8 GB/s │ 17.09 GB/s │ 16.99 GB/s │ │

│ │ │ 17.28 Gchar/s │ 15.8 Gchar/s │ 17.09 Gchar/s │ 16.99 Gchar/s │ │

│ │ ╰─ 1024 33.54 ns │ 35.18 ns │ 34.2 ns │ 34.23 ns │ 100 │ 12800

│ │ 30.52 GB/s │ 29.1 GB/s │ 29.93 GB/s │ 29.91 GB/s │ │

│ │ 30.52 Gchar/s │ 29.1 Gchar/s │ 29.93 Gchar/s │ 29.91 Gchar/s │ │

│ ╰─ Unicode │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─ 0 0.926 ns │ 1.049 ns │ 0.936 ns │ 0.943 ns │ 100 │ 409600

│ │ 0 B/s │ 0 B/s │ 0 B/s │ 0 B/s │ │

│ │ 0 char/s │ 0 char/s │ 0 char/s │ 0 char/s │ │

│ ├─ 8 6.857 ns │ 7.833 ns │ 7.182 ns │ 7.183 ns │ 100 │ 102400

│ │ 4.52 GB/s │ 3.957 GB/s │ 4.316 GB/s │ 4.315 GB/s │ │

│ │ 1.166 Gchar/s │ 1.021 Gchar/s │ 1.113 Gchar/s │ 1.113 Gchar/s │ │

│ ├─ 64 16.46 ns │ 24.76 ns │ 17.27 ns │ 17.41 ns │ 100 │ 25600

│ │ 15.3 GB/s │ 10.13 GB/s │ 14.58 GB/s │ 14.41 GB/s │ │

│ │ 3.887 Gchar/s │ 2.584 Gchar/s │ 3.704 Gchar/s │ 3.674 Gchar/s │ │

│ ╰─ 1024 140.3 ns │ 340.8 ns │ 142.9 ns │ 145.2 ns │ 100 │ 3200

│ 28.74 GB/s │ 11.83 GB/s │ 28.23 GB/s │ 27.78 GB/s │ │

│ 7.297 Gchar/s │ 3.004 Gchar/s │ 7.163 Gchar/s │ 7.05 Gchar/s │ │

...Benchmark Registration

Divan benchmarks can be registered anywhere using the

#[divan::bench]

attribute, like #[test]:

fn main() {

// Run registered benchmarks.

divan::main();

}

// Define a `fibonacci` function and

// register it for benchmarking.

#[divan::bench]

fn fibonacci() -> u64 {

fn compute(n: u64) -> u64 {

if n <= 1 {

1

} else {

compute(n - 2) + compute(n - 1)

}

}

compute(divan::black_box(10))

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ fibonacci 179.3 ns │ 204 ns │ 180.6 ns │ 181.5 ns │ 100 │ 3200And that’s all that’s needed, because OS-dependent linker shenanigans enable you to register benchmarks anywhere.

Benchmark Options

How each benchmark is executed can be controlled via

attribute options,

such as max_time

and sample_size:

#[divan::bench(

max_time = 0.001, // seconds

sample_size = 64, // 64 × 84 = 5376

)]

fn fibonacci() -> u64 {

// ...

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ fibonacci 179.9 ns │ 184.5 ns │ 181.2 ns │ 181.1 ns │ 84 │ 5376Benchmark in CI

Divan’s sample size scaling enables you to run benchmarks in CI due to reduced timing noise. To demonstrate, all examples are benchmarked in CI:

Module Tree Hierarchy

Rust naturally groups functions and types into modules. Divan reflects this grouping in its tree output formatting.

If we want to compare our recursive fibonacci implementation against an iterative implementation, they can be placed together in a module:

mod fibonacci {

const N: u64 = 10;

#[divan::bench]

fn iterative() -> u64 {

let mut previous = 1;

let mut current = 1;

for _ in 2..=divan::black_box(N) {

let next = previous + current;

previous = current;

current = next;

}

current

}

#[divan::bench]

fn recursive() -> u64 {

fn compute(n: u64) -> u64 {

if n <= 1 {

1

} else {

compute(n - 2) + compute(n - 1)

}

}

compute(divan::black_box(N))

}

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ fibonacci │ │ │ │ │

├─ iterative 4.334 ns │ 9.383 ns │ 4.497 ns │ 5.855 ns │ 100 │ 102400

╰─ recursive 154.6 ns │ 185.9 ns │ 159.8 ns │ 159.7 ns │ 100 │ 3200Options can be set across all benchmarks in a module using the

#[divan::bench_group]

attribute macro, such as

max_time

and

sample_size:

#[divan::bench_group(

max_time = 0.001,

sample_size = 64,

)]

mod fibonacci {

#[divan::bench]

fn iterative() -> u64 {

// ...

}

#[divan::bench]

fn recursive() -> u64 {

// ...

}

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ fibonacci │ │ │ │ │

├─ iterative 4.238 ns │ 7.504 ns │ 4.895 ns │ 4.822 ns │ 100 │ 6400

╰─ recursive 149.4 ns │ 361.6 ns │ 154.6 ns │ 157.4 ns │ 97 │ 6208Filter by Regex

When running Divan on the command line, you can filter path::to::function

against a regular expression:

cargo bench -q -p examples --bench threads -- 'id$'threads fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ thread_id │ │ │ │ │

╰─ std │ │ │ │ │

├─ thread │ │ │ │ │

│ ╰─ current_id │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─ t=1 9.131 ns │ 10.43 ns │ 9.701 ns │ 9.587 ns │ 100 │ 51200

│ ├─ t=4 9.781 ns │ 10.1 ns │ 9.863 ns │ 9.856 ns │ 100 │ 51200

│ ├─ t=10 9.781 ns │ 71.3 ns │ 10.43 ns │ 12.2 ns │ 100 │ 25600

│ ╰─ t=16 9.777 ns │ 115.2 ns │ 11.09 ns │ 15.79 ns │ 112 │ 14336

╰─ thread_local │ │ │ │ │

╰─ id │ │ │ │ │

├─ t=1 1.543 ns │ 1.706 ns │ 1.553 ns │ 1.575 ns │ 100 │ 409600

├─ t=4 0.627 ns │ 11.14 ns │ 1.685 ns │ 1.559 ns │ 100 │ 409600

├─ t=10 0.688 ns │ 1.868 ns │ 1.716 ns │ 1.634 ns │ 100 │ 204800

╰─ t=16 0.688 ns │ 1.93 ns │ 1.706 ns │ 1.656 ns │ 112 │ 229376Generic Benchmarks

Divan can benchmark functions with generic types.

The following example benchmarks

From<&str> for

&str and String:

#[divan::bench(types = [

&str,

String,

])]

fn from_str<'a, T>() -> T

where

T: From<&'a str>,

{

divan::black_box("hello world").into()

}Divan can also benchmark functions with generic const

values. The

following example benchmarks initializing stack-allocated

arrays of lengths 1000,

2000, and 3000:

const LEN: usize = 2000;

const fn len() -> usize {

3000

}

#[divan::bench(consts = [

1000,

LEN,

len(),

])]

fn init_array<const N: usize>() -> [i32; N] {

let mut result = [0; N];

for i in 0..N {

result[i] = divan::black_box(i as i32);

}

result

}When ran, these benchmarks will output:

scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

├─ from_str │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─ &str 0.738 ns │ 0.799 ns │ 0.759 ns │ 0.757 ns │ 100 │ 409600

│ ╰─ String 26.8 ns │ 32.18 ns │ 30.39 ns │ 30.42 ns │ 100 │ 25600

╰─ init_array │ │ │ │ │

├─ 1000 572.5 ns │ 598.6 ns │ 583 ns │ 584.5 ns │ 100 │ 800

├─ 2000 1.155 µs │ 1.197 µs │ 1.166 µs │ 1.165 µs │ 100 │ 400

╰─ 3000 1.759 µs │ 1.801 µs │ 1.77 µs │ 1.77 µs │ 100 │ 400The collections.rs

example contains many more generic benchmarks:

cargo bench -p examples -q --bench collectionsBenchmark Context

Benchmarks can take a Bencher argument to provide context and more control

over how benchmarks are run.

#[divan::bench]

fn clone_string(bencher: divan::Bencher) {

let s = String::from("...");

bencher.bench(|| {

s.clone()

})

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ clone_string 26.71 ns │ 56.66 ns │ 28.17 ns │ 28.87 ns │ 100 │ 12800Benchmark Inputs

Each invocation can be given an input using with_inputs, which can then be

used by-reference with bench_refs or by-value with bench_values.

#[divan::bench]

fn append_ref(bencher: divan::Bencher) {

bencher

.with_inputs(|| {

String::from("...")

})

.bench_refs(|s: &mut String| {

*s += "abc";

});

}

#[divan::bench]

fn append_value(bencher: divan::Bencher) {

bencher

.with_inputs(|| {

String::from("...")

})

.bench_values(|s: String| {

s + "abc"

});

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

├─ append_ref 23.87 ns │ 24.85 ns │ 24.19 ns │ 24.19 ns │ 100 │ 25600

╰─ append_value 24.2 ns │ 42.26 ns │ 24.52 ns │ 24.78 ns │ 100 │ 25600Measure Throughput

Divan uses counters to

track quantities processed during each iteration. Currently there are:

BytesCount, CharsCount, and ItemsCount.

The following example generates strings from 50 random Unicode scalars and measures the throughput in scalars and bytes.

use divan::counter::{BytesCount, CharsCount};

#[divan::bench]

fn to_uppercase(bencher: divan::Bencher) {

let len: usize = 50;

bencher

.counter({

// Constant across inputs.

CharsCount::new(len)

})

.with_inputs(|| -> String {

(0..len).map(|_| fastrand::char(..)).collect()

})

.input_counter(|s: &String| {

// Changes based on input.

BytesCount::of_str(s)

})

.bench_refs(|s: &mut String| {

s.to_uppercase()

});

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ to_uppercase 911 ns │ 1.088 µs │ 942.4 ns │ 952.4 ns │ 100 │ 800

217.3 MB/s │ 181 MB/s │ 209 MB/s │ 205.7 MB/s │ │

54.88 Mchar/s │ 45.94 Mchar/s │ 53.05 Mchar/s │ 52.49 Mchar/s │ │By default, bytes throughput is displayed in powers of 1000 (KB), as seen above.

If you prefer powers of 1024 (KiB), set DIVAN_BYTES_FORMAT in your

environment:

DIVAN_BYTES_FORMAT=binary cargo bench -p examples -q --bench scratchscratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ to_uppercase 911 ns │ 1.885 µs │ 937.1 ns │ 958.9 ns │ 100 │ 800

206.2 MiB/s │ 99.15 MiB/s │ 199.4 MiB/s │ 194.9 MiB/s │ │

54.88 Mchar/s │ 26.52 Mchar/s │ 53.35 Mchar/s │ 52.14 Mchar/s │ │The string.rs

example contains many more benchmarks with counters:

cargo bench -q -p examples --bench stringMeasure Allocations

Update: Divan 0.1.6 introduced AllocProfiler for counting

allocations and the number of bytes allocated during benchmarks.

We can create a generic benchmark to measure creating collections from an iterator:

use divan::AllocProfiler;

use std::collections::*;

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOC: AllocProfiler = AllocProfiler::system();

#[divan::bench(types = [

Vec<i32>,

LinkedList<i32>,

HashSet<i32>,

BTreeSet<i32>,

])]

fn from_iter<T>() -> T

where

T: FromIterator<i32>,

{

(0..100).collect()

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

╰─ from_iter │ │ │ │ │

├─ BTreeSet<i32> 374.6 ns │ 4.415 µs │ 415.6 ns │ 445.9 ns │ 100 │ 100

│ alloc: │ │ │ │ │

│ 13 │ 13 │ 13 │ 13 │ │

│ 1.512 KB │ 1.512 KB │ 1.512 KB │ 1.512 KB │ │

│ dealloc: │ │ │ │ │

│ 3 │ 3 │ 3 │ 3 │ │

│ 856 B │ 856 B │ 856 B │ 856 B │ │

├─ HashSet<i32> 989.1 ns │ 1.218 µs │ 1.051 µs │ 1.064 µs │ 100 │ 400

│ alloc: │ │ │ │ │

│ 1 │ 1 │ 1 │ 1 │ │

│ 648 B │ 648 B │ 648 B │ 648 B │ │

├─ LinkedList<i32> 1.135 µs │ 1.697 µs │ 1.145 µs │ 1.158 µs │ 100 │ 400

│ alloc: │ │ │ │ │

│ 100 │ 100 │ 100 │ 100 │ │

│ 2.4 KB │ 2.4 KB │ 2.4 KB │ 2.4 KB │ │

╰─ Vec<i32> 26.69 ns │ 44.59 ns │ 28.97 ns │ 28.64 ns │ 100 │ 12800

alloc: │ │ │ │ │

1 │ 1 │ 1 │ 1 │ │

400 B │ 400 B │ 400 B │ 400 B │ │We can see from the results that Vec and HashSet only allocate once,

whereas BTreeSet and LinkedList allocate 13 and 100 times respectively.

We can also see that Vec allocates 400 bytes, exactly enough to store 100

32-bit integers.

Measure Thread Contention

Divan can give insight into how a function slows down when called simultaneously from multiple threads. Running code across multiple threads may worsen performance due to threads contending on atomics and locks.

This is achieved with the

threads option.

Thread count of 0 indicates using available

parallelism,

which is 10 on my machine.

use std::sync::{Mutex, RwLock};

fn thread_counts() -> Vec<usize> {

vec![/* available parallelism */ 0, 1, 4, 8]

}

#[divan::bench(threads = thread_counts())]

fn mutex() -> i32 {

static LOCK: Mutex<i32> = Mutex::new(0);

*LOCK.lock().unwrap()

}

#[divan::bench(threads = thread_counts())]

fn rw_lock() -> i32 {

static LOCK: RwLock<i32> = RwLock::new(0);

*LOCK.read().unwrap()

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

├─ mutex │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─ t=1 9.639 ns │ 11.51 ns │ 9.883 ns │ 9.893 ns │ 100 │ 51200

│ ├─ t=4 9.715 ns │ 163.3 ns │ 23.07 ns │ 35.82 ns │ 100 │ 12800

│ ├─ t=8 10 ns │ 1.322 µs │ 17.81 ns │ 113.8 ns │ 104 │ 1664

│ ╰─ t=10 11.34 ns │ 916.3 ns │ 19.16 ns │ 154.1 ns │ 100 │ 3200

╰─ rw_lock │ │ │ │ │

├─ t=1 17.2 ns │ 17.86 ns │ 17.53 ns │ 17.46 ns │ 100 │ 25600

├─ t=4 17.2 ns │ 319.9 ns │ 28.92 ns │ 96.77 ns │ 100 │ 6400

├─ t=8 16.53 ns │ 338.1 ns │ 17.88 ns │ 65.83 ns │ 104 │ 3328

╰─ t=10 15.89 ns │ 442.3 ns │ 168.5 ns │ 147.5 ns │ 100 │ 6400As contention from multithreading increases, we see the slowest and mean

numbers trend upward with thread count. This is also indicated by the iters

number decreasing as the duration of each iteration increases.

Every thread runs under the same conditions: competing against t - 1 other threads. As a result, sample count is always the next multiple of thread count: the default sample count of 100 becomes 104 for 8 threads.

To increase the chance for contention, all threads are synchronized immediately

before and

after the

sampled section using a Barrier. This also prevents work done by other

threads before and after the sample from affecting the current thread’s

measurements.

The

threads.rs

example contains many multi-threaded benchmarks for Arc, Mutex,

ThreadId, and more:

cargo bench -q -p examples --bench threadsCPU Timestamp

Divan uses the portable Instant timer by default. For extra precision, you

can instead use the CPU’s timestamp counter

(TSC):

DIVAN_TIMER=tsc cargo bench ...The TSC is architecture-specific:

- x86:

rdtscfollowed byrdtscp, with frequency obtained by measuring againstInstant - AArch64:

cntvct_el0with frequency obtained fromcntfrq_el0

The time.rs

example benchmarks TSC against Instant and SystemTime:

cargo bench -q -p examples --bench timetime fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

├─ duration_since │ │ │ │ │

│ ├─ instant 3.393 ns │ 4.94 ns │ 3.414 ns │ 3.444 ns │ 100 │ 204800

│ ├─ system_time 4.268 ns │ 4.512 ns │ 4.309 ns │ 4.336 ns │ 100 │ 102400

│ ╰─ tsc (aarch64) 0.021 ns │ 0.064 ns │ 0.034 ns │ 0.039 ns │ 100 │ 1638400

╰─ now │ │ │ │ │

├─ instant 18.18 ns │ 19.32 ns │ 18.34 ns │ 18.44 ns │ 100 │ 25600

├─ system_time 17.36 ns │ 18.34 ns │ 17.53 ns │ 17.62 ns │ 100 │ 25600

╰─ tsc (aarch64) 0.738 ns │ 0.779 ns │ 0.759 ns │ 0.755 ns │ 100 │ 409600Note that

time::duration_since

for TSC is extremely fast because it is simply doing

u64::saturating_sub,

since an optimized timing implementation would want to keep the value as TSC

units for as long as possible before dividing by the TSC frequency.

Design

I deliberately designed Divan with multiple considerations in mind, the most important being simpler benchmarking and getting out of your way.

Simpler Benchmarking

From the beginning, my goal was to make Rust benchmarking simple and easy. Divan accomplishes this in many ways:

Register Benchmarks Anywhere

Rust’s #[test]

attribute makes unit testing very simple and straightforward. Divan achieves the

same simplicity with

#[divan::bench] using

linker shenanigans to make benchmarked functions visible to

divan::main().

linkmeprovidesDistributedSlice, which coerces to&[T]using link-time pseudo-symbols for the range of start and end addresses.For other platforms,Divan implementsEntryList, a thread-safe append-only linked list constructed beforemainruns.

Update: As of

0.1.3,

Divan uses the same implementation for all supported

platforms.

I found the approach used by linkme to not work on many platforms.

Linker-based approaches to registration are limited to few platforms. Divan is tested in CI to work on macOS, Linux, and Windows.

Bencher By-Value

When benchmarking with context, the Bencher argument is

provided by-value instead of

by-reference.

Divan then leverages the builder

pattern

to provide various benefits:

- Reduce cognitive load when reading and writing benchmarks.

- Prevent accidental reuse by making

Bencherno longer usable after you’ve called a method likebench. If a benchmark method is not called, the compiler will warn that the value must be used. - More powerful polymorphism with benchmark inputs, where later operations

like

input_counterandbench_valuesact on the input type. See type-driven APIs.

Sample Size Scaling

An operation may be too fast for the timer to measure. On Mac M1, the timer

precision (smallest measurable duration) of Instant and CPU timestamp is

41 nanoseconds, which cannot accurately measure an addition that takes 1

nanosecond.

To make timing accurate, Divan groups many iterations together between timings as a unit called a “sample”. The formula determines the number of iterations (sample size) needed to overcome timer precision:

To determine the final sample size, Divan doubles the number of iterations until the duration of a sample reaches . This is calculated by re-timing each so that the final result is not solely dependent on the initial duration.

If you don’t consider that re-times, and instead assume returns a consistent predictable value, then can be reasoned about as:

Robust Benchmarking Paper

I was inspired to scale sample size based on timer precision because of the paper Robust Benchmarking in Noisy Environments by Jiahao Chen and Jarrett Revels.

This paper concludes with the description of , an oracle function that maps from the theoretical minimum execution time to the number of iterations to overcome timer precision. They found the generalized logistic function to work well:

…where reasonable values of a and b are approximately:

This paper’s approach is significantly more complex than that of Divan. Although simpler, Divan achieves similarly meaningful results by the commonality of relying on timer precision:

Divan does not use timer accuracy because it wasn’t clear how accuracy can be

obtained without a more accurate reference timer, when Instant is usually

implemented with the most accurate timer. I’m open to making sample size scaling

smarter, but the current approach works well enough.

This paper also concludes that the smallest duration is the most meaningful number, because any extra time spent can be attributed to error due to poor performance conditions, such as being unscheduled by the operating system. I agree 99.999% of the time, except for when you want to measure thread contention.

Getting Out of Your Way

Divan allows you to focus on what’s most important: your code. It is designed to be difficult to misuse and employs various techniques to reduce its timing footprint.

Type-Driven APIs

When benchmarking with Bencher, you cannot call any of the

bench_values/bench_refs/input_counter functions until you provide

benchmark inputs. Likewise, the standard bench function cannot be called

if you have already provided inputs.

This is made possible by the fact that the () type does not implement the

Fn family of traits. Bencher uses () as the default for a generic

type until with_inputs is called, at which point Bencher uses the

provided Fn type.

Deferred Drop

When values are returned by the benchmarked function, Drop destructors

will not run until after the sample is recorded.

This is achieved by storing results in a buffer, which will be dropped after the

sample. If buffering is not done carefully, it could affect the accuracy of

benchmarks by accidentally also timing buffer capacity checks and

reallocation.

To ensure accurate benchmarks, Divan implements this very efficiently by

iterating over a preallocated

slice of

MaybeUninit “drop slots” to store outputs in.

Only one of the following functions will benchmark LinkedList deallocation

time:

#[divan::bench]

fn defer() -> std::collections::LinkedList<i32> {

(0..1000).collect()

}

#[divan::bench]

fn drop() {

// Benchmarks can be implemented in terms of each other.

_ = divan::black_box(defer());

}scratch fastest │ slowest │ median │ mean │ samples │ iters

├─ defer 26.12 µs │ 31.87 µs │ 29.56 µs │ 30.13 µs │ 100 │ 100

╰─ drop 65.37 µs │ 75.2 µs │ 69.43 µs │ 68.3 µs │ 100 │ 100Note that if needs_drop for the output is false (e.g. (), i32,

&'static str), Divan will not allocate storage for deferring

output drop. Likewise if output is a zero sized type

(ZST).

Benchmark inputs are stored together contiguously with outputs in memory. The resulting access pattern is monotonically increasing, which is easily prefetched into cache.

Efficient Enums

Divan internally uses an

UntaggedTimestamp

union, which can be either an Instant or a CPU timestamp. The variant

is kept track of by an external

TimerKind

instance, unlike a conventional enum which internally stores the variant

tag. Externally storing the variant tag is a micro-optimization to prevent extra

time spent on storing the timestamp during the sample.

Future Plans

Divan has many opportunities for features. Future versions will have:

-

Better output options:

-

HTML output with interactive graphs. Hovering over a graph will reveal data points.

-

Machine-readable output like JSON and CSV.

-

Colored terminal output with customizable themes.

-

-

Improved statistics:

-

Baseline comparison.

-

Sample variance.

-

-

More profiling tools:

-

GlobalAllocprofiling similar todhat-rs, but with minimal performance impact.Update: As of

0.1.6, you can measure allocations with Divan’sAllocProfiler. -

Custom profiler plugins like

pprof.

-

-

Async

Futurebenchmarking to measure server and client performance. -

Registering benchmarks without attribute macros to support more platforms like WebAssembly.

-

Runtime argument values, as an alternative to const generics. Const parameters are great for benchmarking different array sizes, but they have limited type support and greatly increase benchmark compile times.

Acknowledgements

I especially want to thank Thom Chiovoloni for his benchmarking advice over many blue moons, and for the CPU timestamp implementation. Thom will also be helping me maintain Divan!

Thanks also to the folks who provided feedback on drafts of this post: Carlos Chacin, Predrag Gruevski, Tim McNamara, Ben Wis, Ramona Łuczkiewicz, Corey Alexander.

Conclusion

Now that you know how to measure performance with Divan, I invite you to try it out in your own Rust projects. I’m eagerly curious to know what insights it will reveal to the community!

Please get involved and help make Divan the standard benchmarking tool for Rust:

- Sponsor regularly or donate once 💖

- Implement or collaborate on my future plans 🚀

- Tell your friends and colleagues about Divan 🗣

If you enjoyed this post, subscribe to my newsletter.